PRESENT LIFE

PRESENT LIFE

- WORK

- FULL CATALOGUE

- INSTALLATION VIEWS

- WORK

- FULL CATALOGUE

- INSTALLATION VIEWS

- WORK

- FULL CATALOGUE

- INSTALLATION VIEWS

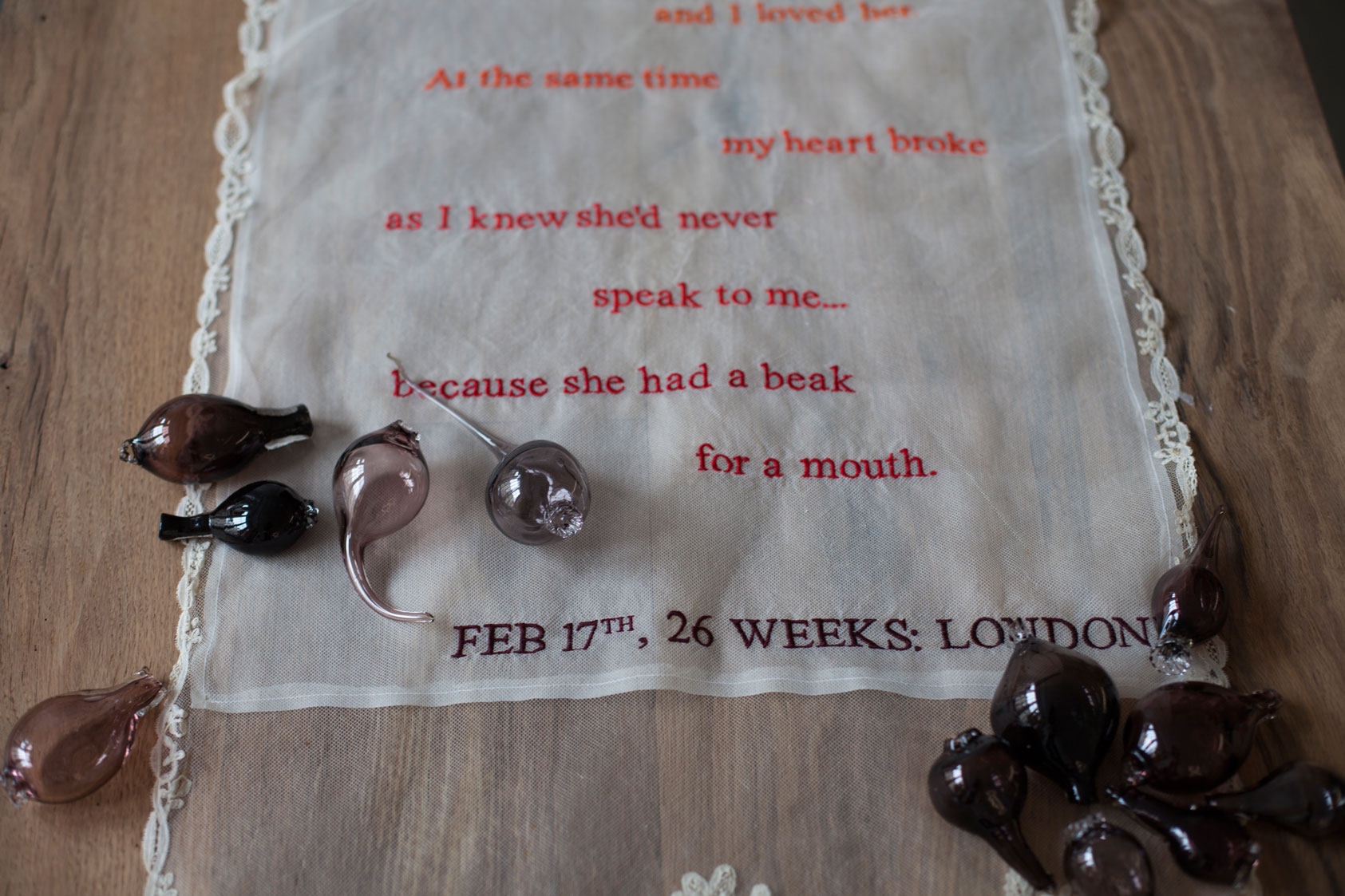

The installation of hanging vintage lingerie reveals the artist’s fascination with femininity throughout time. The antique undergarments — relics from our past and windows into cultural ideas of female objectification — are reworked using musical text from a very specific time and place. Buckman hand-embroiders the lingerie with lyrics that refer to women from the iconic rappers Tupac Shakur and Notorious B.I.G. The text spans from the violent and misogynistic to the wholly sympathetic and pro-choice. This juxtaposition is witty in its provocation and empowered awareness while comparing the Janus-faced relationship between feminism and Hip-Hop both in the 90’s and today.

Buckman grew up in a feminist and activist household in East London. Hip-Hop and its culture was very much the predominant influence on the youth there, and Buckman listened to the music of Tupac and Biggie so much that their words permeated her consciousness and formed part of her every day inner dialogue.

As she grew older and more of aware the everyday sexism around her, she found herself further engaged with her feminist lineage. This produced an internal disconnect between her feminist side and some of the messaging in the music she favored. Simultaneously, she registered that there was positive and uplifting feminist content in a lot of the songs, especially in Tupac’s music. For the Every Curve installation, Buckman keeps the installation personal by limiting the text to that of Biggie and Tupac, as they were the ones that most captured her attention in her youth.Buckman is drawn to using hand embroidery because of its roots in the female experience and expression and it’s place within the lineage of feminist art. She also uses vintage lingerie to evoke the female form and ideas of objectification, whilst highlighting the history of women, female liberation, empowerment and sex. The lingerie garments themselves have all been worn close to the body and by, potentially, several different women, most of who have probably passed, like the rappers themselves. Therefore, the space in which the installation hangs has a strong sense of absence: the absence of these unidentified women, the two iconic men and their respecting legacies.

The garments tell us what ideas of objectification were like at the time of their creation. In order to highlight this notion, Buckman uses garments from varying decades — corsets from the turn of the century depict how the body was restricted and repressed, fluid and free slips and robes from the 20s and 30s brings to light a time when the female form was celebrated and ideas of feminism were being implanted in society, and lingerie from the 50s and 60s display the body once again squashed and morphed into a shape that was more appealing to men. This was a response to the freedom women had during the war while the men were away, and the fashion of the 50s was circulated via advertising as a way to get women back in the home, thinking about their appearance and essentially living in discomfort. The work uses both the sexist and misogynistic language as well as the positive language of the different song lyrics. Buckman is not shunning the violent content, but rather exploring the dialogue between the two and finding a way to flip the negativity — to create something beautiful, and hopefully thought provoking, as a way of working through the struggle. Because, in a country where young black men are born to believe there is something intrinsically deviant about them, how can one shun the music for expressing the violence that they have been told they possess?